Introduction

Hancock, broadcast on the BBC between May and June 1961, was Tony Hancock’s last series for the BBC and was also the last one written for him by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson.

From 1954 onwards, Hancock had enjoyed great success with Galton & Simpson’s scripts, both on radio and on television. There had been six series of Hancock’s Half Hour on the radio – between 1954 and 1959 – as well as six television series, which ran from 1956 – 1960.

But by 1961 Hancock was restless and wanted changes. Sid James had been present in virtually every television and radio episode, but he was dropped from Hancock, at Tony’s request. And when this series had finished Tony Hancock dispensed with Galton & Simpson as well. For many people this marked the start of the long downward spiral in Hancock’s personal and professional life which ended with his suicide in Australia in 1968, at the age of 44.

Among those who insisted that the ties Hancock severed led directly to his untimely death was Spike Milligan, who said: “One by one he shut the door on all the people he knew; then he shut the door on himself.”

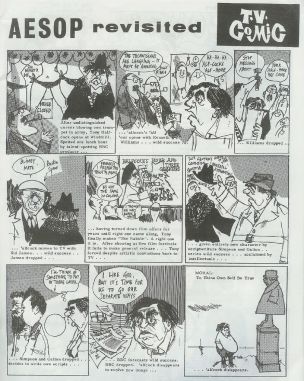

Harsh criticism of Tony Hancock can be found in the following cartoon from Private Eye in June 1962, drawn by Willie Rushton.

But whatever happened after Tony Hancock left the BBC in 1961, between 1954 and 1961 he, along with Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, created some of the finest episodes of situation comedy ever seen in any country. And their final series, thanks in part to Tony’s insistence on changing the character slightly, ensured that they ended their creative partnership on a high.

Hancock (Broadcast on BBC Television between 26th May – 30th June 1961)

Galton & Simpson like to tell the story that Hancock asked them to write an episode where he was the only character seen. They thought it wouldn’t work and decided to write something to prove to Tony that it was impossible. The result was The Bedsitter and it proved to be an excellent showcase for Hancock and one of the best things that G&S ever wrote.

When G&S started to write for Tony, they tended to craft elaborate plots which usually hinged on Sid trying to con Tony into doing something. Over the years they pared down the storylines so they became less fantastic and more mundane.

The most mundane episode of the radio series has to be Sunday Afternoon At Home. This isn’t a criticism – it’s a beautifully judged picture of a typical Sunday afternoon where there’s nothing to do except kill time. In that episode though, Hancock had Sid James, Bill Kerr, Hattie Jacques and Kenneth Williams to spar with, but in The Bedsitter there’s nobody but himself.

It shouldn’t work, but it does. Nothing much happens – Tony attempts to read some Bertrand Russell, loses interest and then attempts the more hard-boiled charms of Lady Don’t Fall Backwards. But even that proves to be a problem, as he concedes: “It’s a waste of time me reading, I can never remember anything. I’ve got too much on my mind, you see, nuclear warfare, the future of mankind, China, Spurs.”

Later on, a misdirected call offers the chance of a date, but in the end it comes to nothing. Hancock though maintains a brave face: “That was a lucky escape! I nearly got sucked into a social whirlpool there, diverted from my lofty ideals into a life of debauchery! The flesh-pots of West London have been cheated of another victim! Eve has proffered the apple and Adam has slung it straight back at her!”

One of the strange things about the G&S series is that unlike most sitcoms there was never any attempt to maintain even a basic level of continuity. Hancock’s status would change week by week – one week he could be penniless and unknown and the next – as we see in The Bowmans – he may be the popular star of a top-rated radio series.

A none too subtle swipe at a popular rural radio soap opera,The Bowmans certainly gives Hancock full reign to unleash his country accent, which is great fun. It’s also a rarity in that we see Hancock finish on top for once. His character is killed off from the soap, but public opinion forces the producers to bring him back as his own twin brother and then he takes great delight in ensuring the majority of the villagers fall to their deaths down a disused mine shaft!

The Radio Ham is not quite a solo performance likeThe Bedsitter, although Hancock does spend the majority of the episode alone in a room by himself. He does have company though, via the ham radio he’s built. Substitute the internet for the radio and it seems right up to date.

Re-recorded for LP release in 1961, The Radio Ham has quite rightly become one of the classics of British sitcom. Comedy rarely gets better than this, with so many quotable lines.

The Lift is an episode that it’s possible to imagine in any series of HHH. Like The Train Journey from series 5 it has a similar premise – take a group of disparate characters who are trapped together (in a train or a stuck lift) with Hancock at his most annoying and wait to see what happens.

Noel Howlett, Jack Watling, Hugh Lloyd, John Le Mesurier and Colin Gordon are among the unlucky people who have to share a lift with Tony. It’s not an episode that innovates, like The Bedsitter, but it does what it does very well. And it’s helped no end by the fine performers stuck in the lift with Hancock.

Hancock: Yes, we all know you’re a doctor. You’ve been talking about nothing else since we’ve been here. I don’t understand you. I don’t go around telling people what I am all the time.

Doctor: I think we’ve all reached an opinion as to what you are.

Along with The Radio Ham, The Blood Donor is probably the most famous Hancock episode (helped by the excellent LP re-recording previously mentioned). With this one though, I do prefer the LP version – due to the circumstances of the television taping.

In the week prior to the tv episode recording, Hancock was involved in a car crash. He wasn’t badly hurt – although more make-up than usual can be seen on his face to hide the superficial scars – but he didn’t have time to learn his lines, so he read them off boards held above the camera.

Once you know this, then it’s impossible not to be distracted by the fact that he obviously never looks at anyone else in the scene as he’s always looking to the side and his next line. There is the odd stumble, but overall his performance is brilliant – considering that when he speaks any line he’s just seen it for first time and he has to instantly decide on pacing and inflection.

However you experience it, it’s a classic. So many quotable lines and a collection of first rate performers for Hancock to bounce off (June Whitfield, Patrick Cargill, Frank Thornton, Hugh Lloyd).

If you view Hancock as an album, then the first five episodes are hit singles whilst the last, The Succession – Son and Heir, is resolutely an album track.

It’s not a bad episode, but compared to the other five it’s not quite in the same class. The premise is bright enough though, Tony decides the time has come to perpetuate the line and produce a heir, so a bride is sought. But thanks to his luck with the opposite sex in the end he decides to stay single.

There’s still plenty of quotable moments though, particularly when Tony’s thumbing through his little black book for suitable partners: “Elsie Biggs: 42-36- ….. oh no, that’s her phone number. Still, I don’t fancy her pounding about the house all day long. She’s a bit too hefty for me. She had me over a few times.”

Conclusion

Classic comedy that nobody should be without. There’s a boxset containing all the surviving BBC TV episodes or if you just want to sample this series, then The Best of Hancock is a single DVD with five of the six episodes (excluding The Succession). Either way, no collection of British television comedy can be complete without something from the Lad Himself.